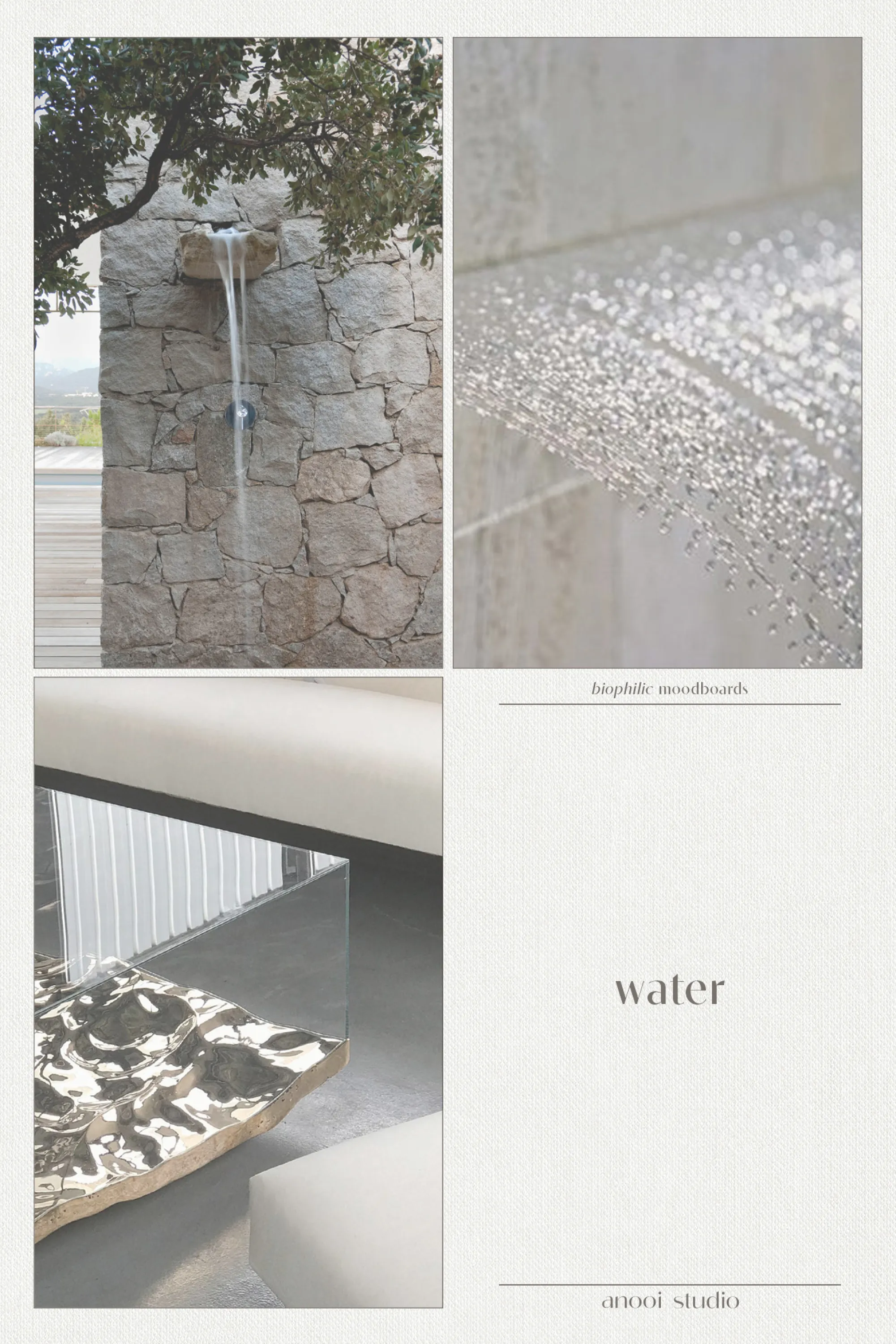

Biophilic moodboards: water

Water is extremely restorative for the mind, and a biophilic approach encourages its use as a design element. The presence of water and water features adds interest, introduces sensory richness, and incorporates a real natural element in the space.

This episode of Biophilic Moodboards looks into the use of water in designed spaces…

Sensory water features

Spaces that stimulate all the senses are inherently more interesting, and water features can add restorative stimuli to the space.

Whenever speaking about sensory stimuli, accessibility is a factor to consider, allowing as many sensory interactions as it’s possible and appropriate. Water features are no exception, getting more compelling when they can be experienced with more senses at once: seen, heard, touched, smelled and maybe even tasted.

Sensory experiences can be further enriched by design. For instance, intentional accent lighting makes a water feature even more intriguing to watch, amplifying its effects. Pointing a light at the right spot can emphasize a flowing movement, or give more dimension to single drops when they splash.

Appropriate sizing

Flowing water creates compelling sounds, constantly-changing forms, and interesting sensory stimuli regardless of size.

A smaller water feature can be just as effective as a bigger one and in some cases it is even more appropriate. Water makes quite a noise, and a big water feature could easily feel disturbing in a smaller space.

Water without water

If real water has unique qualities, some of its features can be recalled with other materials: giving a sense of flow and movement, creating ripples, bubbles and other effects.

Especially when paired with lighting, these water-like applications can add a lot to a space, introducing an unexpected and lively feature.

Water can add a lot to designed spaces: movement, sound, and a real element of life that, in turn, will transfer unique liveliness to the space.

Further resources:

Available in the shop, anooi’s publications explore the nuances of a biophilic ethos, highlight anooi’s perspective on the topic, and cover the studio’s ongoing research in biophilic thinking and design.