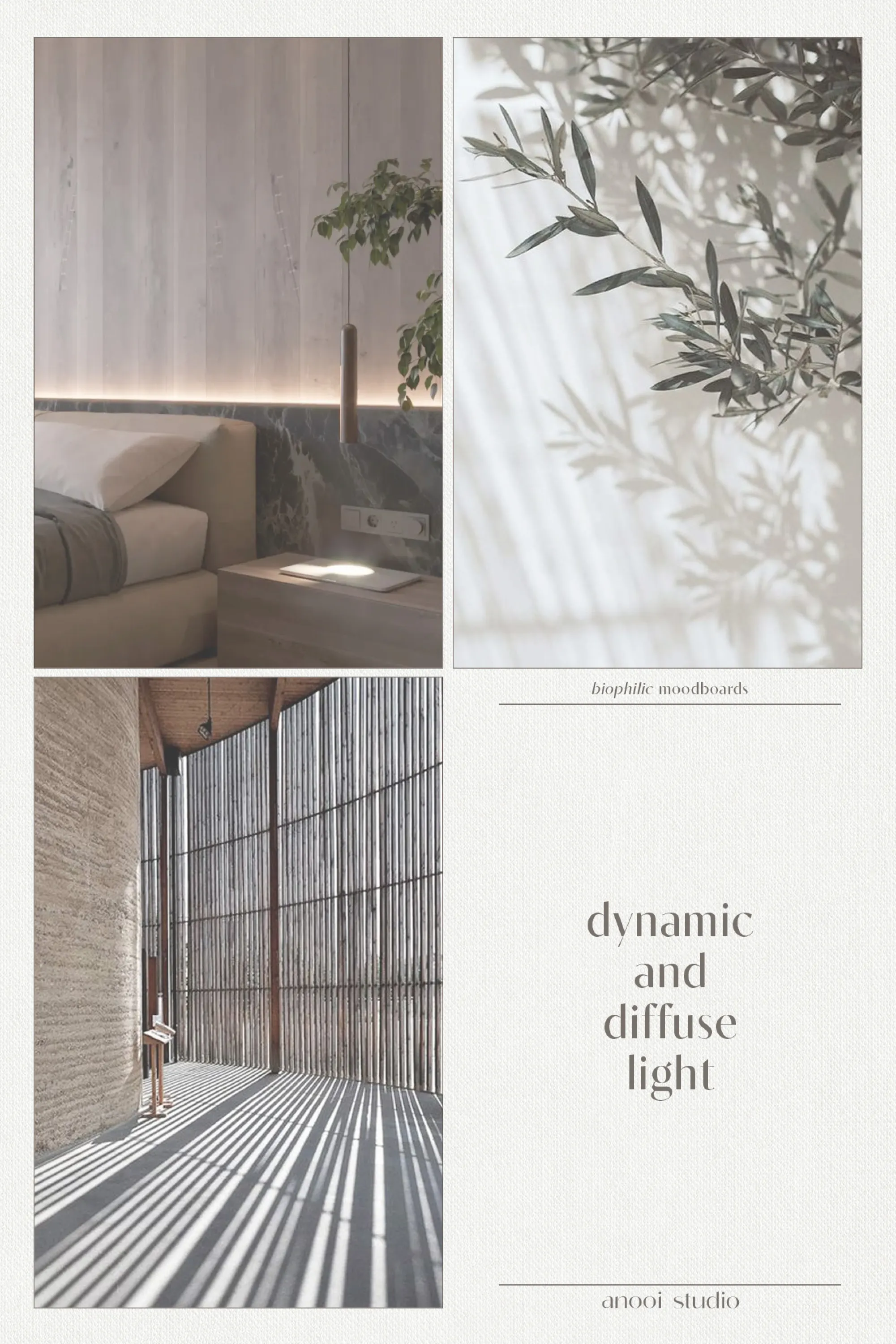

Biophilic moodboards: leveraging the power of light in interiors

Light plays a crucial role in human wellbeing. A biophilic approach takes the impact of light into close consideration, recognizing that both natural and artificial light do much more than glowing in the dark.

This episode of Biophilic Moodboards looks into light, its relationship with human wellbeing, and design implications…

Natural light and wellbeing

Natural light is what regulates human circadian rhythm: the biological clock that drives hormones’ production, making us awake during the day and ready to rest as the night comes. Natural light affects sleep quality, mental balance, concentration, performance, and mood.

There are two features that make sunlight so unique. Natural light is:

Dynamic – because it changes during the day, flowing between low and warm (at dawn and in the evening) and bright and cool (during the day).

Diffuse – because it spreads evenly in the space.

A natural foundation

Natural light is key to every interior space and becomes particularly important where people spend long periods of time. Notably, this concerns workplaces and schools. In the home, it includes living rooms, kitchens, dining areas, bedrooms and children’s bedrooms, as well as home office spaces.

Besides regulating the circadian rhythm, access to natural light adds life to the space, connects interiors with what’s happening outdoors, and provides awareness and appreciation of nature’s changes.

Wellbeing-centered artificial lighting

Artificial lighting is usually set to a fixed intensity and colour, taking away the beneficial dynamism of sunlight. This is one of the reasons why lighting is best when designed in layers. Juxtaposing ambient, task, and accent lighting creates a varied and interesting distribution of light in the space.

Human Centric Lighting is another option. Mimicking the changing colour and intensity of sunlight, human-centric systems create a lighting setup that flows during the day, supporting the circadian rhythm.

Designing with light

Natural light can also introduce an ever-changing piece of art in the space, in the form of sculptural light and shadow plays that evolve during the day and across seasons. Many naturally occurring light reflections also follow a fractal pattern, bringing further interest into the space.

The reflection of a water feature, light filtering through the branches of a tree or the hollows of a patterned screen…these are all examples of moving and changing light that adds life and engages the senses.

As a whole, an intentional and curated use of natural and artificial light in designed spaces can blend functional and wellbeing needs – all while reconnecting people to the richness of the natural world.

Further resources:

Available in the shop, anooi’s publications explore the nuances of a biophilic ethos, highlight anooi’s perspective on the topic, and cover the studio’s ongoing research in biophilic thinking and design.